Kalea’s Paper Quilling Reflection

I anticipated that paper quilling would require a certain amount of trust in the process itself. That is, with paper-based crafts, the maker often must combine seemingly disparate actions or materials in order to create the intended object. However, I was surprised that attention to colour is crucial to paper quilling as designs lose their form without the definition provided by colour or shades. Indeed, the colour of my paper strips became crucial to my design as I experimented with modes of data visualization to represent perspective in Charlotte Brontë’s novel Villette (1853).

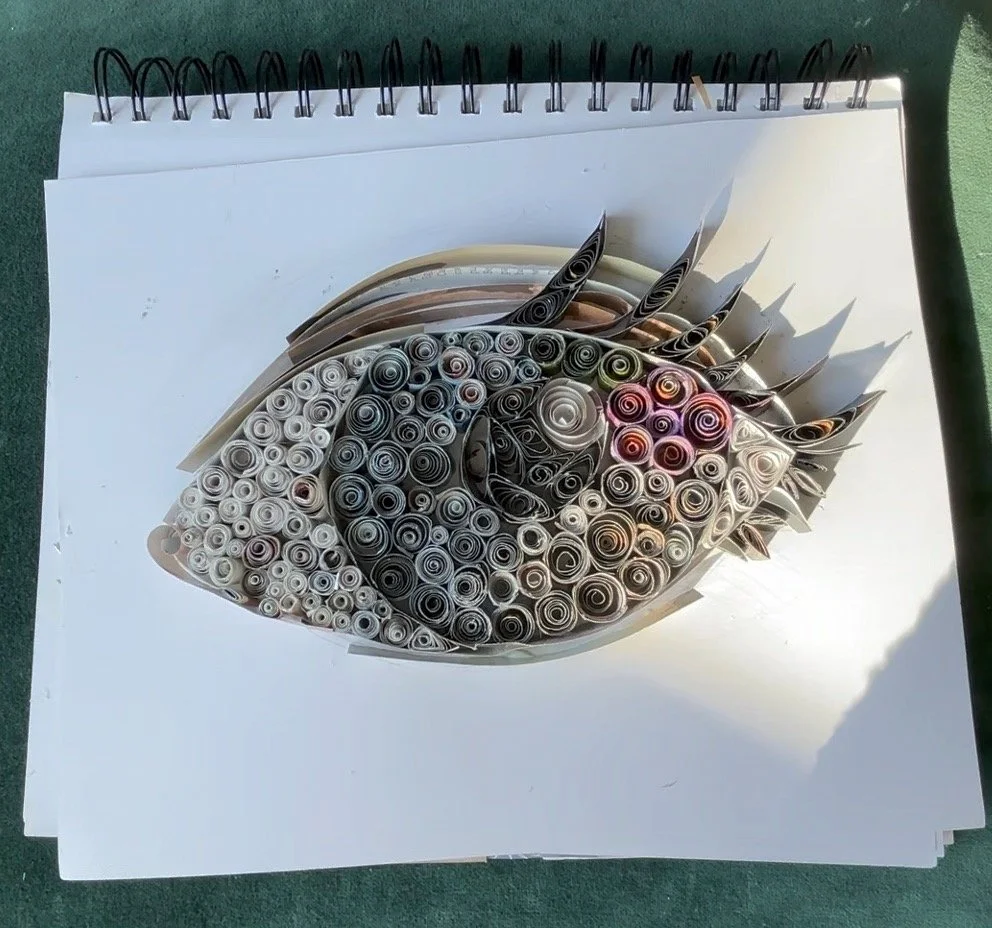

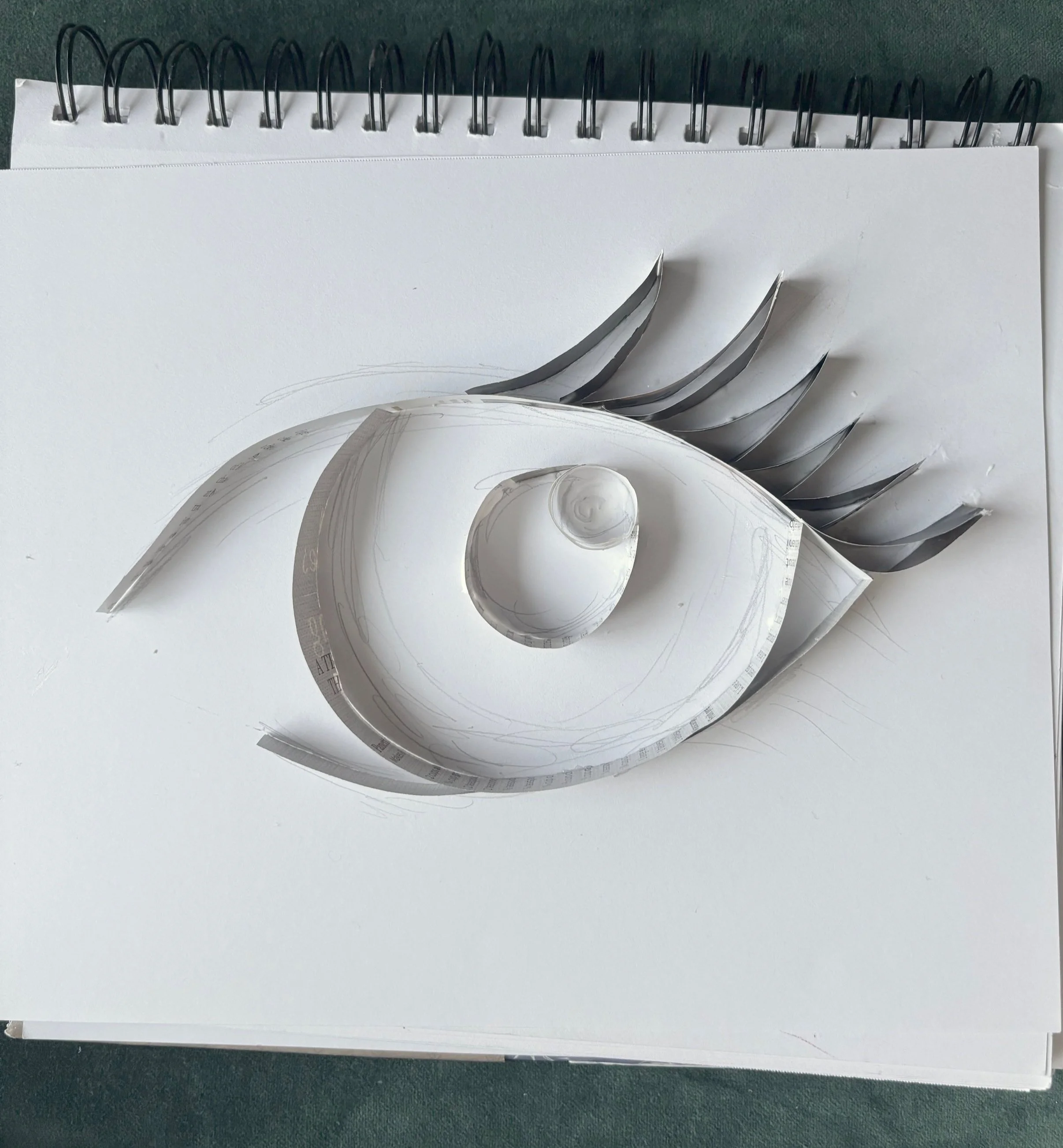

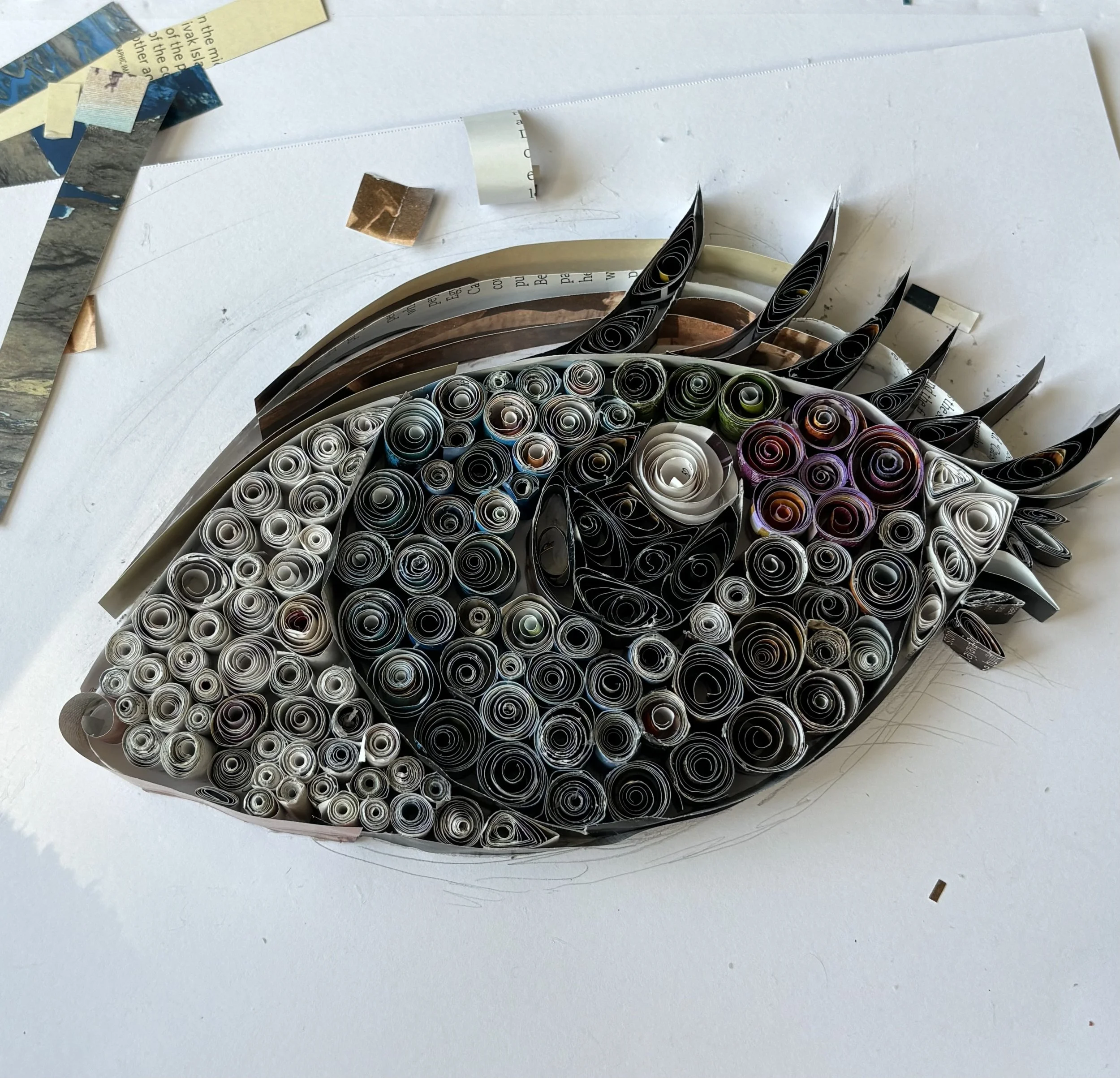

By paper quilling an eye, I aimed to capture the importance of the first-person perspective to the novel. While making my small-quilled design, I realized that paper quilling—like literary analysis—requires awareness of both form and structure. My paper quilling combines physical structures and conceptual forms: paper walls separate individual coils and primary shapes form the skeleton of the design, but the design itself also has the capacity to visualize patterns, relationships, and narrative point of view. In the novel, Brontë emphasizes the importance of point of view by frequently mentioning eyes and characters’ eye colours, intimating the differences among characters’ disparate points of view. I used quilling to represent how often particular eye colours were mentioned within the text, visualizing not only the protagonist’s attention to detail in the first-person narrative mode but also the variety and quantity of descriptions of eye colour in the novel. Villette includes blue, dark (brown or black), violet, and green eyes. For every mention of an eye colour, I quilled three strips of paper in the corresponding colour and then used those paper quills to fill in the iris.

While the process of paper quilling gave me an appreciation for Villette’s structure and forms, as I curled and placed many small paper shapes within and next to one another, I also thought about the enmeshed history of paper and people. We can thus think about the metonymic function of paper outside the written word as such a substitution conveys the luxury of ornamentation without words or wealth.

I had difficulty achieving the symmetry of extant paper quilling. Despite my efforts to cut each strip to the same width, the heights of nearly all of my strips differed once glued to their surface and I struggled to create uniform coils (some have crimps in unintended places where I changed the tension while rolling or pinched the wrong end). However, I found the repetitive motions of quilling—selecting, rolling, slipping—more meditative than tedious, and, as a result, I did not worry over my uneven walls and the mismatched quills within them. Instead, I had the space to think about the relationships between the values I was representing, the form of paper quilling, and how paper shapes us.